Santa Anita Park: A History

From a Thoroughbred Racetrack to a Donation Site and Everything In Between

As we have watched the fires unfold across Southern California, I have been most intrigued by the organic, community-based aid groups that have sprung up across the affected communities. In the San Gabriel Valley, a donation center first popped up at the Pasadena Rose Bowl’s parking lot following the start of the Eaton fire in Altadena on January 7th when Jerry Martinez, Juan Diaz, and Jimmy Medina decided to hand out hotdogs to those affected by the fires. However, word soon spread across social media, brining more volunteers and aid to the Rose Bowl. Within days, the National Guard would arrive to begin staging their command center and relief efforts at the Rose Bowl, which would require a new location was needed for community-based relief efforts.

On January 10th, the donation center secured a new space in a parking lot in Arcadia’s storied Santa Anita Park thoroughbred horse racing track. The new donation center would run at Santa Anita Park from January 10th until yesterday, Friday, January 17th, when it officially closed its doors. The organizers and volunteers of this grassroots donation center are now regrouping as they pivot to the next phase of their volunteer efforts. It is always stories like this, of community based aid and support, that make me proud to be a Southern Californian.

Now, let’s dive into the history of the venue that made these grassroots aid and donation efforts possible.

On Christmas Day 1934, the Los Angeles Turf Club opened at Santa Anita Park, ushering in a new level of style and sophistication to the Southern California thoroughbred racing scene. Combining the best qualities from the Art Deco, Colonial Revival, and Streamline Moderne styles, architect Gordon Kaufmann was able to braid these styles together to create a truly unique horse racing venue.

When seen through the streamlined 1930s lens, the Turf Club’s underlying Georgian and Regency Revival style lines become more abstract, more sinuous, allowing for cues of modernity to interplay within more classical styles and structures to great effect. I am particularly struck by the entrance’s semi-circular portico, chinoiserie-inspired entry doors, Chippendale-inspired railings, and lacy wrought iron work, which lend a sophisticated air to the building’s almost clinically crisp lines.

The Park’s grandstands, with their bands of sculpted wrought iron screens, deep overhangs, and stark stucco exterior creates an effervescent exterior scene, beckoning spectators inside to place their bets and watch race after race after race. I love how Kaufmann was able to highlight the range of the Streamline Moderne style at Santa Anita Park, revealing how this unique style’s wide range of application.

The building interiors appear to have been carted in from a movie set, allowing the Hollywood world of glitz and glam to rub elbows with the heady world of equestrian racing and breeding.

However, America’s entry into World War II would cast a different light on Hollywood’s favorite racetrack. Santa Anita Park would continue to operate as a racetrack until early 1942, when President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066, authorizing the forced incarceration of all Japanese American citizens in concentration camps across the country. As a first step, Japanese American citizens were first gathered in “Assembly Centers,” a euphemism for a transitional detention center when Japanese American citizens.

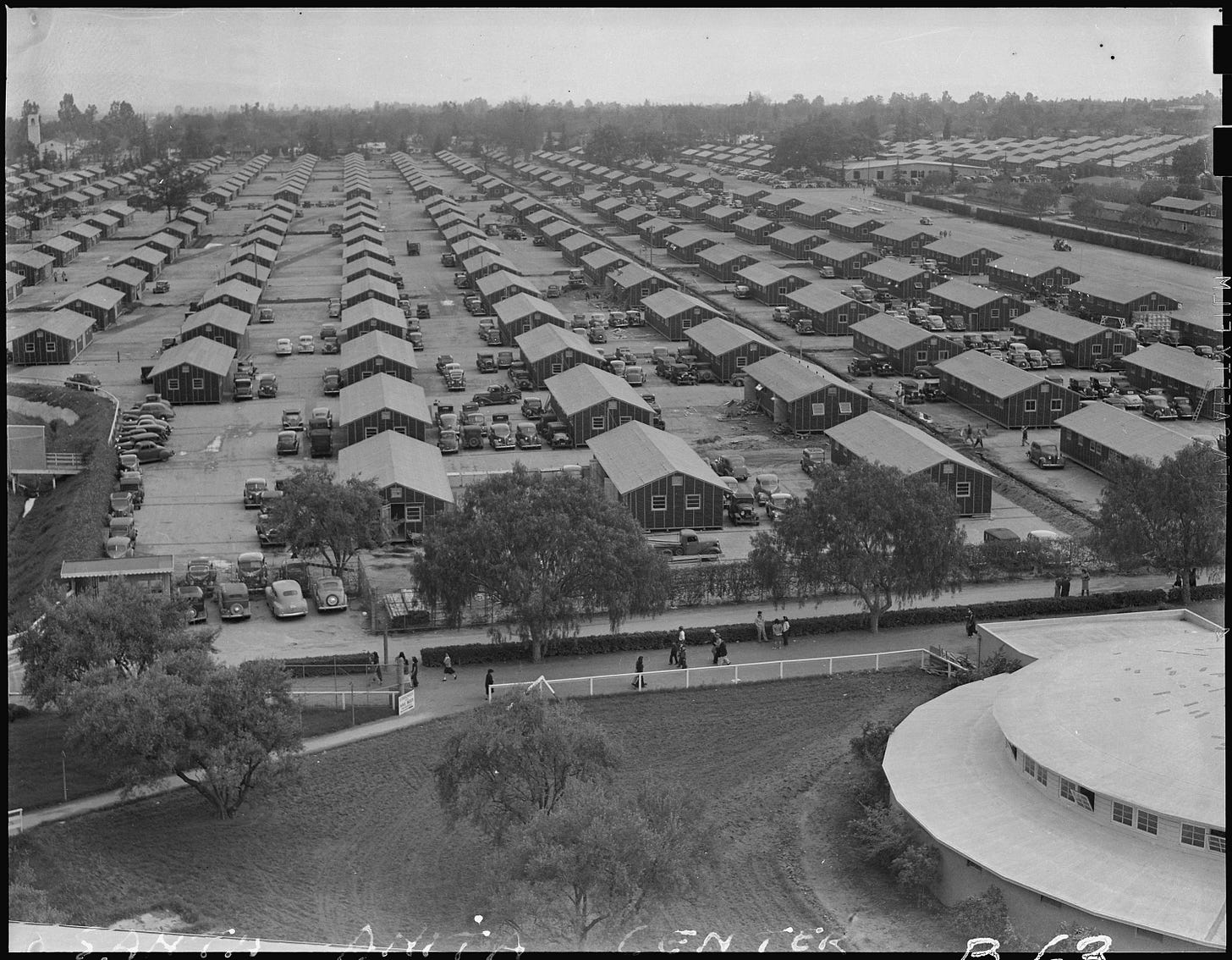

On March 27, 1942, the Santa Anita Assembly Center would open, housing 18,719 American Citizens of Japanese descent at its peak. This transition into a detention center would include the building of 500 new barrack buildings as well as the conversion of the horse stables and grandstands into living areas.

On August 4, 1942, a riot would break out at the Santa Anita Assembly Center following the implementation of harsh new administrative policies, which restricted the use of the Japanese language for meetings, in printed materials, and even in music. Following observations of the Internal Security Police removing “hotplates, dishes, records, books, screwdrivers, hammers, sacks of rice, etc.” and rumors of cash and jewelry being taken as well, a group of young men stormed the camp’s administrative offices to protest these injustices. These individuals would then be separated from their families and sent to the Tule Lake concentration camp in Newell, California.

The camp was soon closed on October 27, 1942 following the transfer of the prisoners to the Heart Mountain, Rohwer, Granada, and Jerome concentration camps. While this dark chapter of US history has closed, it is our responsibility to remember this travesty of justice and share its memory with future generations to come so we do not ever see such inhuman and unjust actions taken against any our own citizens ever again.

The histories we covered today are among the reasons why I am so drawn to Southern California’s architectural heritage. Here, one building can provide a touchstone into worlds, communities, and histories that we could never have imagined. Who would have guessed that the site of one of our greatest grassroots aid and humanitarian feats for fire victims was also the site of one of our most unjust and discriminatory chapters of US history—not me! And that is exactly why I will continue to share these architectural histories and stories, so we can continue to make connections between where we’ve been and where we’re going, all while keeping an eye out for any eye catching designs and stylistic flourishes. After all, there’s no place like sunny Southern California!

Located at 285 W Huntington Drive, the building has been expanded and remodeled, yet still retains much of it’s original 1930s charm, including the original color palette of Persian Green and Chiffon Yellow.

Project: The Los Angeles Turf Club at Santa Anita Park, 19234

Architect: Gordon Kaufmann

Location: Arcadia, California

Source: Architectural Digest, Wikipedia, Densho Encyclopedia, Blood Horse Magazine