Before visiting New Orleans, my nearest point of reference was twenty minutes away in Disneyland’s New Orleans Square, a three-quarter acre fantasy land boasting whimsical wrought iron, potted ferns, and hanging gas lanterns, all meant to recall a genteel New Orleans of the antebellum age. On our tours across the city, our guides stressed that “New Orleans is not Disneyland,” and it sure isn’t—it’s even better.

Founded as a European city on American soil, New Orleans has one of the most layered and complex histories of any city in the United States. First and foremost, we must remember that the beauty and riches of New Orleans were built upon the slave trade, on the dehumanizing practice of chattel slavery, with the city nicknamed the “mistress of the slave trade” for the numerous slave traders who imprisoned men and women in high walled pens before making a profit off their sale. This history is abhorrent and uncomfortable, yet one that we as Americans must stand witness to and share so we may honor the memory and legacies of those who were dehumanized by the institution of slavery, an institution whose ramifications we are still grappling with to this day.

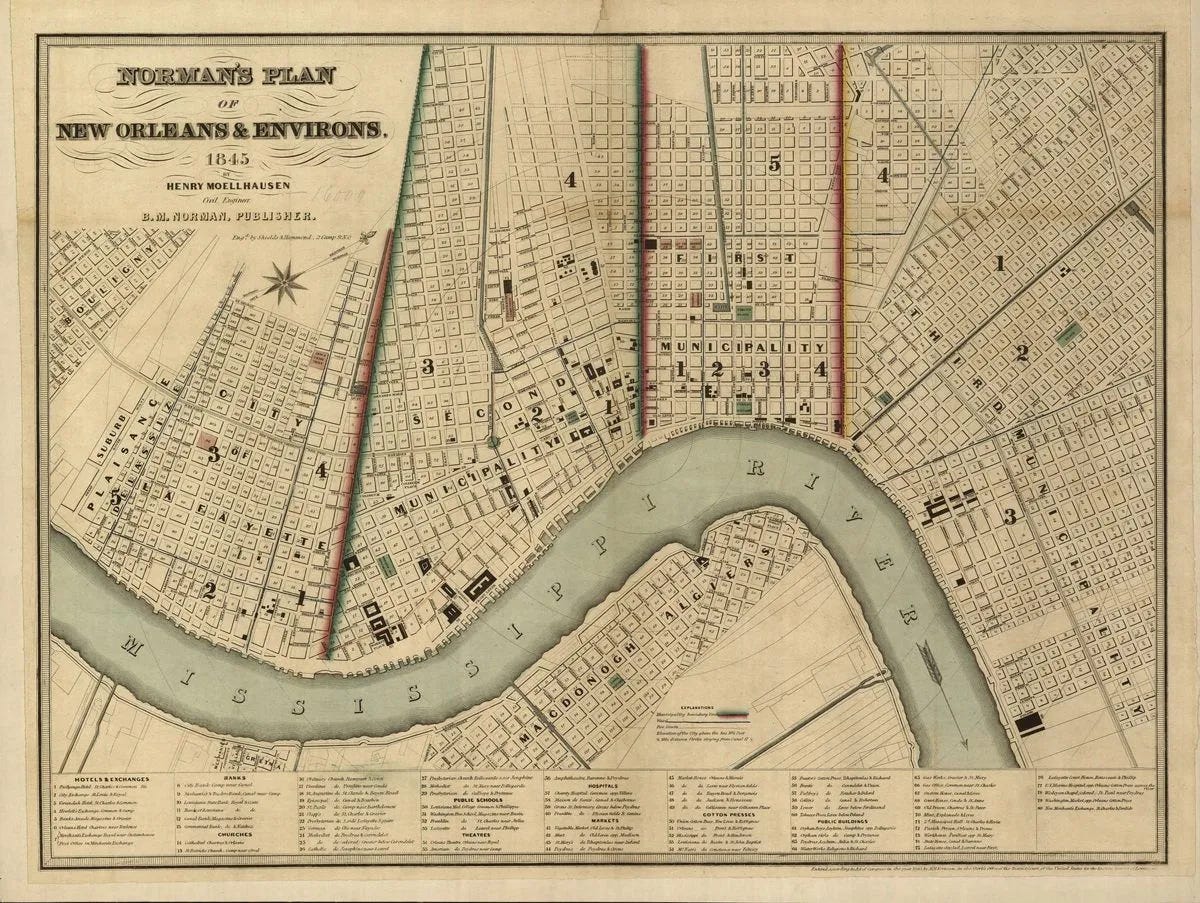

For me, it was important to view the city through this lens as I moved through it, marveling at the incomparable architecture, gardens, and streetscapes of the Garden District, first developed between 1830 and 1900, with its pre-Civil War homes all built by the hands of enslaved men and women. In 1832, Marie Celeste Marigny Livaudais sold the Livaudais plantation to a group of American businessmen who subdivided the land into what would become the small city of Lafayette in 1833, a small hamlet that would be the chosen neighborhood for the wealthy new American elite establishing themselves in New Orleans. The American elite disliked the European style French Quarter with it’s narrow townhomes built around generously sized central courtyards, preferring architectural styles more akin to those of Boston, Philadelphia, and New York City over the regions’ Continental influences. As the prominent French and Spanish Creole families of the French Quarter weren’t too keen to mingle with their new American counterparts, the development of the Livaudais plantation allowed the American transplants a place to establish their own identity in the region. By 1852, the city of Lafayette was annexed into the city of New Orleans proper, ushering in further expansion within the neighborhood.

Today, we’ll dive into some of the Garden District’s prominent home’s to learn more about the region’s robust histories.

Located at 1448 Fourth Street, and perhaps most famous for its dynamic cornstalk wrought iron fence, the Residence of Colonel Robert Short was designed by architect Henry Howard in a rambling Italianate style. Upon the capture of New Orleans by Union forces, the home would be seized by the federal forces until the end of the war when it was returned to Colonel Short.

The residence of Walter and Emily Robinson, located at 1415 Third Street, was designed by architects James Gallier Jr. and Henry Howard and completed in 1859. Located on a a large corner lot, the Italianate style home combines a Corinthian ordered curved front porch with lacy wrought iron galleries to great effect, effectively increasing the already large home’s useable square footage by inviting it’s inhabitants to enjoy the balmy Louisiana air. Walter G. Robinson, originally from Lynchburg, Virginia, made his fortune in cotton and tobacco before heading to New Orleans to make further profits in the deep south.

Combining Greek Revival, Italianate, and Federal style elements, the sprawling Residence of John I. Adams is a sunny spot within the Garden District, with it’s curved garden porch among my favorite details in town.

There are numerous architectural styles within the Garden District, ranging from Italianate to Swiss influenced Gothic Revival, and even an exaggerated form of Greek Revival, all seen through a uniquely New Orleanian eye. Notice how the Rice residence includes columns from from the Doric, Ionic, and Corinthian orders to display the owner’s wealth and style from the sidewalk.

In the image in the top right, we can see this home has a distinct staircase, called a courting staircase, which is more often seen in cities such as Charleston or Savannah instead of New Orleans, yet allowed men to enter on one side, and women bedecked in hoop skirts and pantalettes to enter on the other without fear of exposing their ankles to a possible beau. Also, take a look at the home in the upper right picture—the porch ceiling has been painted blue to mimic the sky beyond—such a charming touch!

One of my favorite details I found in the garden district were the Egyptian-inspired keyhole-shaped doorways and the use of unique stained glass to enhance a home’s curb appeal—true southern hospitality at its finest! The keyhole-shaped doorways have been made famous by the work of Anne Rice, and I can certainly see why as they’ve captivated my imagination.

New Orleans is a city rich in beauty and history, yet there is always two sides to the same coin. This beauty could not have been built without labor and knowledge of enslaved people and their descendants, many of whom have been sadly forgotten by history. Yet, through these historic homes, we can celebrate their contributions to the city and its culture.

As we have seen, the architectural heritage of New Orleans has influenced style and design all across the United States, especially in our fair Southern California. Golden Age architects such as Roland Coate, Gordon Kaufmann, and Marston, Van Pelt, & Maybury synthesized Southern Colonial and Creole townhouse elements to create a uniquely Southern Californian interpretation of Southern style. Stay tuned for a deep dive into this synthesis in our next issue of Robbie Adobe!

New Orleans isn’t Disneyland; it’s complicated, it’s layered, it’s real. I appreciate it all.