The Influence of New Orleans Creole Style on Southern California's Architectural Golden Age

How Southern Living Arrived in the Southland

While seemingly disparate, the architectural styles of Southern California and New Orleans share a rich history that underscores the unique connection between the Spanish Colonial and French Colonial architectural canons across the United States of America. Spanish and French settlers called upon their traditional building styles to create European style homes on the American frontier, homes that were distinct from their Anglo-Saxon counterparts in Britain’s thirteen colonies along the Atlantic seaboard. This shared continental origin allowed the Spanish and French Colonial styles to intermingle and coalesce in New Orleans, a city that would alternate between French, Spanish, and American rule throughout its history.

New Orleans was founded by Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville, an agent for the Mississippi Company, in 1718 and would replace Biloxi as the capital of New France in 1722. Under the terms of the 1762 Treaty of Fontainebleau, France ceded New France to Spain at the end of the Seven Years War, establishing New Orleans as the capital of the new Spanish realm of Louisiana. In 1788, the Great New Orleans Fire would sweep through the city, destroying 856 of the roughly 1,100 structures standing at that time and was followed by a second fire in 1794 that destroyed over 200 structures, leaving the Ursuline Convent as the only true French Colonial building remaining after the blaze.1 When rebuilding the city, Spanish authorities replaced the burnt out wooden buildings with Spanish-influenced structures built of brick, stucco, and wrought iron to increase their fire resistance, effectively creating the New Orleans we know and admire today.

New Orleans’ most famous domestic architectural styles include the creole cottage and it’s larger sibling, the creole townhouse, with both forms drawing inspiration from a mixture of French and Spanish influences. Similarly, the French word creole was borrowed from the Spanish criollo, meaning a person of European ancestry born in the New World, which in turn was influenced by the Portuguese word crioulo, referring to Africans born into slavery in Brazil.23 As we can see, not only architecture, but also the languages, communities, and identities of those living in New Orleans have long been intertwined with numerous colonial powers.

The creole cottage, a single story structure built right up to the lot line in urban locals, was characterized by raised foundations, brick and stucco construction, pitched gable or hipped roofs, and large porches spread out under their generous eaves, allowing seamless indoor-outdoor living in the Louisiana climate.4 Similarly, the Creole townhouse was a multi-story structure built of brick or timber frame and masonry abutting the sidewalk with the service wing arranged behind the main structure centered around a service courtyard.5 There are competing theories as to whether the Creole townhouse was influenced by the French or Spanish architectural canons, with the Spanish School advocates point to the “barrel tile roofing, paving tiles, wrought-iron balustrade work and flat or almost flat rooflines which appeared on buildings” following the Great Fire, while the French School supporters suggest that “Creole townhouses were modeled after dwellings found in prosperous eighteenth-century Parisian neighborhoods. These homes, in turn, had been inspired by a type of closed-court farmstead which can still be seen in northern France… Some of these houses even featured French doors and open galleries facing the courtyard.”6 I contend that the New Orleans Creole style was influenced by both the French and Spanish architectural canons, with the city itself serving as a frontier zone, “a transformative, dynamic contact zone where there were daily interactions among people of varied backgrounds” allowed the conditions to create a unique architectural style suited to life along the lower Mississippi.7

Let’s take a look at some examples of Southern California homes that integrated New Orleans Creole flourishes into a range of other domestic revival styles.

First up is the captivating 1928 residence of Mr. and Mrs. H. C. Lippiatt and Mrs. M. P. Taylor, designed by architect Roland Coate to ramble across it’s Bel Air hilltop in a wide-ranging mélange of the New Orleans Creole townhouse, Spanish Colonial Revival, and Monterrey Revival styles. From the New Orleans Creole townhouse we have the home’s ornate second story wrought iron covered balcony, we owe the home’s romantic, rambling composition and reja covered first floor windows to the Andalusian traditions of the Spanish Colonial Revival style, all while the home’s paneled front door surrounded by sidelights and a transom in addition to the rear elevation’s wooden second story cantilevered covered balcony point towards their Monterrey Revival antecedents. Through this residence, Coate reveals that he was the master of weaving New Orleans Creole townhouse elements into Southern California architecture during its golden age.

Also designed by Coate, the 1929 Monterrey Revival style Pasadena residence of Mr. William B. Hart combines rose colored brick resembling adobe, includes a New Orleans Creole townhouse inspired second story cantilevered covered balcony on the home’s street-facing facade. The wrought iron’s grape motif is perhaps meant to recall a bountiful, bacchanalian harvest, and the inclusion of iron pot holders is a truly Spanish Colonial Revival flourish—and a favorite flourish of mine.

For the 1929 residence of Mr. and Mrs. G. G. Mayo, Roland Coate braided together the Regency Revival and New Orleans Creole townhouse styles with Tudor Revival elements to create a sweeping knoll-top house in San Marino. The home’s expansive Regency Revival white brick exterior is enlivened by the dining room’s diamond-paned bay window and the New Orleans Creole townhouse inspired wrought iron entry porch as well as the delicate wrought iron second story covered balcony on the home’s garden elevation.

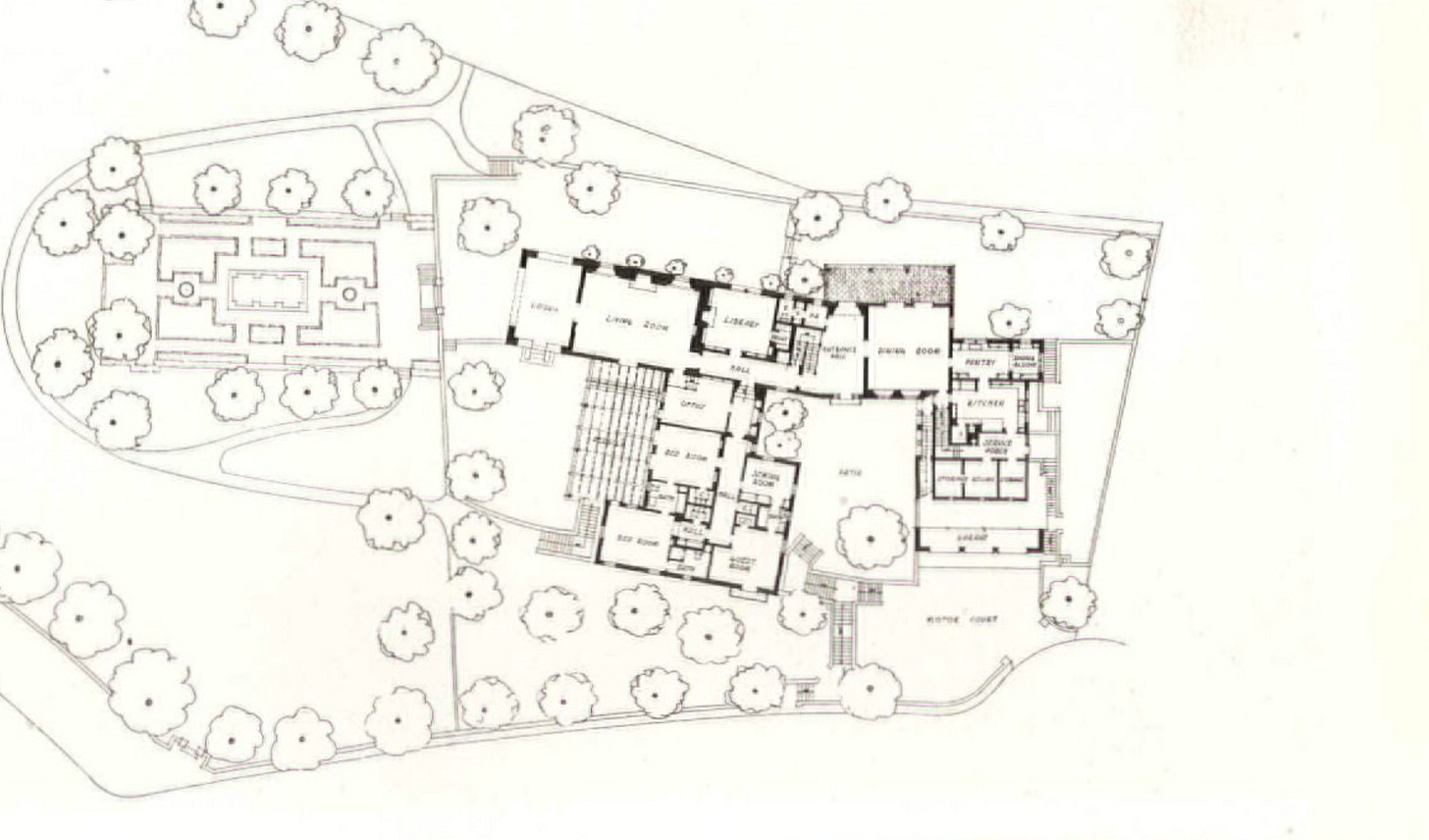

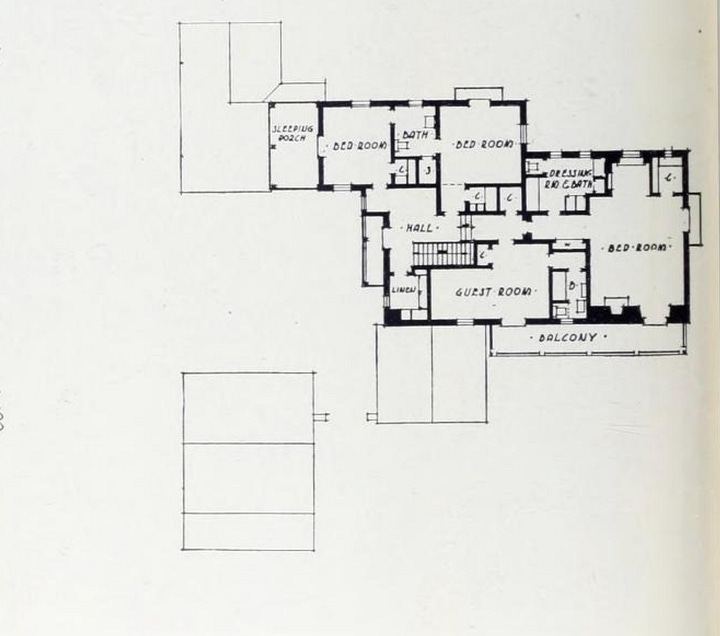

For the 1929 Bel Air residence of Capt. and Mrs. John D. Fredericks, Gordon B. Kaufmann would successfully combine the Georgian Revival, Southern Colonial Revival, French Provincial, and New Orleans Creole townhouse styles to create a well balanced composition built around an H-shaped Mediteranean Revival inspired floor plan. By the late 1920s, the Georgian and Colonial Revival styles were beginning to supplant the, mirroring a rise in US nationalism that would continue through the 1930s. The home’s white brick exterior graciously pairs elements from both the Georgian and Southern Colonial Revival canons with a French Provincial tower and an exquisite New Orleans Creole townhouse style wrought iron entry porch to create a truly cosmopolitan Southern California country home.

Our final home was designed by John Byers, Architect, and Edla Muir, Associate. We have yet to do a deep dive into their work (fear not, they’re on the horizon), but we recently reviewed a charming 1930 Edla Muir designed Spanish Colonial Revival Style home on the market in Little Holmby that touched on their history. In brief, Muir would work weekends and summers as a clerical assistant for the architect John Byers at his Santa Monica based office while she attended Inglewood High School and, following her 1923 graduation, would join Byer’s office as an assistant before becoming a draftsperson in 1926. After Muir earned her architectural license in 1934, Byers and Muir would form the John Byers and Edla Muir, Associated Architects partnership, which lasted until 1942.

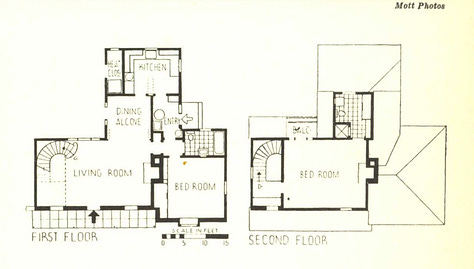

For the 1938 California House & Garden Exhibition, Byers and Edla Muir would loosely base their New Orleans Cottage on the urban Creole cottages found in New Orleans withs its steeply pitched side gabled roof, deep overhang, and front shutters, and add a little New England Colonial Revival by way of Southern California flourish through the inclusion of the first floor bedroom wing. From the outside, the home could easily pass for Dutch Colonial Revival or possibly even Cape Cod Revival, underscoring America’s preference for more Inside, Byers and Muir included a sweeping curved staircase with a sinuous wrought iron balustrade, adding a dash of movie star glamour.

A more concerted nationalistic push towards the Colonial Revival style would begin after World War I, with architect Aymar Embury II writing in 1922 that he found “fewer houses derived from strange traditional styles,” noting that the “bulk of the work, especially the work which is generally regarded as of high quality, is derived either from American Colonial and English Georgian, or from the English cottage type of architecture. The vogue for French architecture of the epoch of Louis XIV and XV has pretty well disappeared. We find few Italian or Spanish houses, and the traditional styles still less appropriate to American methods of living are conspicuous by their absence.”8

However, these same Southern California architects such as Roland Coate, Gordon Kaufmann, John Byers, Edla Muir, and others would combine the Spanish Colonial Revival, Mediterranean Revival, Monterrey Revival, Georgian Revival, Southern Colonial Revival, and even French Provincial style with New Orleans Creole style elements to create structures uniquely at home in the California of the twenties and thirties, a cinematic place where you could be anything and anything was imaginable, especially the architecture of your own home.

Similarly, as many architects pivoted to Monterey Revival forms, with historian David Gebhard noting that “the characteristic Monterey-style house as well as the California ranch house of the thirties exhibited a wealth of ‘correct’ colonial details never found in the nineteenth-century originals,” demonstrating that “the trend in the thirties for the California ranch [or Monterrey Revival] house was to reduce slowly the Hispanic aspect of it and to increase its colonial qualities.”9 In Coate’s designs for the Lippiatt & Taylor and Hart residences, we see that he wove together the seemingly incongruous Monterrey Revival and New Orleans Creole styles to create homes with true stylistic ingenuity, demonstrating how architects could artfully, and creatively, blend architectural canons to create a dynamic new style.

In my mind, Spanish Colonial Revival and New Orleans Creole styles are cousins, each with their own appreciation for wrought iron, stucco, balconies, and shutters. The American revival styles represent the country’s complex architectural imagination in the early twentieth century, a time when America was beginning to define itself as a modern nation. These revival styles also reveal the rich tapestry of American architectural heritage, with a wealth of canons and traditions we are lucky to call our own. And, yet, the people who built both the Spanish Colonial and New Orleans Creole styles were not only responding to warm southern climates, but also to the recent incursion of Yankee Americans Britain’s original 13 colonies, who would bring their own architectural, namely Colonial, traditions with them. Could the union of the Spanish Colonial Revival and New Orleans Creole have been a response to the increase in the more eastern Colonial Revival style? Perhaps, yet, to me, it’s a joyous occasion to see the New Orleans Creole style included on homes in Southern California, reminding ourselves of the layered, multifaceted historic ties that connects all people across these United States.

Kurt Owens, “How the Fires of 1788 and 1794 Changed New Orleans,” The Historic New Orleans Collection, November 10, 2022, https://hnoc.org/publishing/first-draft/new-video-shows-how-fires-1788-and-1794-changed-new-orleans.

“Creole,” Merriam-Webster.com Dictionary, accessed March 26, 2025, https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/creole#word-history.

“‘Creole’ and ‘French Creole.’” Creole and French creole. Accessed March 26, 2025. https://www.datacenterresearch.org/pre-katrina/tertiary/creole.html.

Patricia L. Duncan, “French Creole: Louisiana Architecture – a Handbook on Styles,” French Creole | Louisiana Architecture – A Handbook On Styles, accessed March 27, 2025, https://www.crt.state.la.us/cultural-development/historic-preservation/education/louisiana-architecture-handbook-on-styles/french-creole/index.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Stephan Timothy Lenik, “Frontier Landscapes, Missions, and Power: A French Jesuit Plantation and Church at Grand Bay, Dominica (1747-1763),” Frontier Landscapes, Missions, and Power: A French Jesuit Plantation and Church at Grand Bay, Dominica (1747-1763) (dissertation, 2010).

Aymar Embury, “Current Tendencies in Country House Design in the East,” Architectural Record, October 1922.

David Gebhard, “The American Colonial Revival in the 1930s,” Winterthur Portfolio 22, no. 2/3 (July 1987): 109–48, https://doi.org/10.1086/496322.